Defying a potential disaster. How cartoonists fought Dutch National Socialism on the eve of the Second World War

The Netherlands had a lively press landscape in the 1930s, with newspapers and magazines of various political persuasions. Not only were denominational groups well represented, but the liberals and social democrats also served their supporters with news and opinion. The same was true of the communists and National Socialists, relative newcomers on the scene. In this way, all of these groups not only maintained their relations with their existing followers, but they also used their publications to recruit new supporters and converts.

Political cartoons

One such publication was the illustrated weekly, in which attempts were made to expose ideological opponents through the use of appealing cartoons that mixed exaggeration with disparagement. In the left-liberal weekly De Groene Amsterdammer, for example, political cartoonist L.J. Jordaan tried to reveal the true nature of the Nazis.

In the social democratic corner, an even more emphatic appeal was made to the noteworthy efforts of several cartoonists, for a similar purpose. Both De Notenkraker and Vrijheid, Arbeid, Brood! took an outspoken stand against fascism and National Socialism at home and abroad, by frequently publishing cartoons by Albert Hahn, Tjerk Bottema and George van Raemdonck, among others.

For these two magazines, these drawings were an obvious way to declare their political convictions, as they conveyed both their aversion to communism and, equally, their belief in a social democratic future. But there was also a magazine that was dedicated solely to fighting National Socialism and, in 1939 – aided by countless cartoons – averting political disaster at home: De Blaasbalg. A magazine that is rarely mentioned in the historiography, yet deserves our full attention.

De Blaasbalg

De Blaasbalg, which was published as a small format newspaper, had a short existence. The first edition was reportedly published in a print-run of 1 million copies, but hardly any have survived. The copies that are available in the NIOD library bear witness to a varied use of visual material that goes beyond the requisite handful of photos of authors and political leaders. With a certain light-heartedness belying a deeply serious undertone, the visual elements attempted to bring some variety to the grave current events that formed the focus of the publication.

The magazine’s editors were led by journalist Dr G.J. van Heuven Goedhart, editor-in-chief of the Utrechts Nieuwsblad (and attached to the underground newspaper Het Parool during the German occupation). It was published by a foundation with the telling name ‘Weest op uw hoede’ – ‘Be on your guard’ – established by Bob and Mia van Meurs-van der Burg, a couple from Eindhoven. Looking ahead to the municipal and provincial elections in April and June 1939, respectively, the initiators saw a need to defend democracy and Dutch freedoms against the dreaded advance of National Socialism.

'To fan the flames of freedom'

In the words of the initiators, who operated relatively anonymously, De Blaasbalg endeavoured ‘to fan the flames of freedom, until they blaze high again in our free Netherlands.’ Four years on, the results of the 1935 provincial elections, when the National Socialist NSB had managed to attract some 8 per cent of the vote, still formed such a spectre that action was now deemed unavoidable.

The initiators showed themselves to be freedom-loving democrats who opposed anti-Semitism and declared their support for the royal family. They managed to engage authors such as Menno ter Braak, a very young Annie M.G. Schmidt, Professor Jan Boeke and educationalist Dr C.P. Gunning. The editors’ efforts were by no means limited to the written word, and they drew on the talents of several cartoonists.

A total of six issues were published. The fourth issue concluded with a photo collage that presented readers with a choice: whether they wanted to see their children grow up in freedom or under a dictatorship. In a special issue on Amsterdam, photos were combined with a drawing. Earlier, in the second issue, a fictional ‘club song’ for Dutch National Socialists had been illustrated with a large group of similar male figures in uniform, right arms outstretched – possibly inspired by the same designer.

The origins of the drawings and other illustrations are far from clear. At least two caricatures were taken from the Polish press, for example, including a short comic strip in four panels by Zenon Wasilewski, about the diplomatic summit in Munich in September 1938 that ended fatally for Czechoslovakia.

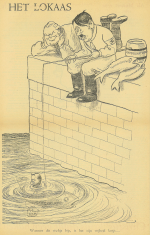

However, Dutch cartoonists also worked for the publication. In an anonymously published cartoon in the second issue, Dutch citizens were warned against a blow from a windmill whose spinning sails had been replaced with a swastika. The first edition had featured an unsigned drawing captioned ‘His Master’s Voice’, showing Anton Mussert, the leader of the NSB, as a puppet of the German head of state. This may have been the work of L.J. Jordaan, who produced other prints that were published in two later issues, elaborating on the link between Mussert and Hitler.

The true nature of the NSB

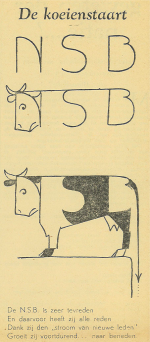

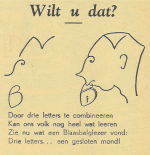

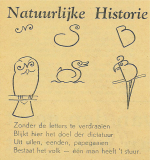

Another striking contribution was a set of five drawings that used letters and symbols to expose the true nature of the NSB as the servile follower of what was unmistakably the German example. In the final issue of De Blaasbalg, the wolfsangel, a heraldic symbol that was often used by Dutch National Socialists, was developed into a fully-fledged swastika – at Menno ter Braak’s suggestion, according to cartoon expert Hans Mulder.

But earlier issues had already featured a so-called ‘letter lesson’ in somewhat light-hearted fashion. In four different ways, the cartoonist played on the letters ‘NSB’ to reveal the extent of the morally bankrupt, slavish submissiveness at the political heart of this far-right movement.

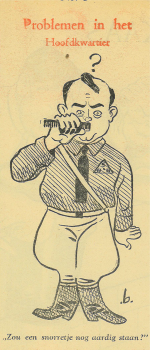

Amongst the most eye-catching drawings in De Blaasbalg were those by Charles Boost (1907-1990). His first two contributions were at the back of the second issue. First of all, Boost placed Mussert in front of a distorting mirror, deluding himself that he had grown considerably taller.

The same issue also featured an illustrated poem in which one of Mussert’s followers had traded his inferiority complex for a pair of boots, whose stamping drowned out the neglected moans of his fellow men. In the next issue, Boost temporarily gave Mussert a Hitler moustache to underscore his childish reverence for the German leader.

A shivering Mussert

The thematic issue on Amsterdam’s municipal elections is unequivocally disparaging of Mussert. A shivering, miniature version of Anton is placed next to Adolf, conveying his anticipated lack of local political success and utter disappointment. The leader of the Dutch National Socialists is also shown in a highchair, to minimise the electoral ambitions in the capital as much as possible.

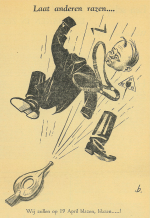

Boost concludes his contribution to this engaged series of pamphlets in style. In the final issue of De Blaasbalg, he goes all-out. Under the motto ‘Let others rage...’, the anti-fascist publication’s aim is visualised as explicitly as possible: on the day of the elections, the Dutch voters blow the leader of the NSB off his pedestal so forcefully that his uniform disintegrates into bits.

In reality, however, the electorate did not wipe the NSB off the map altogether: the NSB won 3.94% of the vote in the Provincial States, and 6.91% on Amsterdam’s municipal council. De Blaasbalg seemed destined to fade into oblivion, while the radicalisation of the NSB continued before and after the arrival of the German occupying forces in May 1940.

Antisemitic actions

That later obscurity is undeserved, certainly from the perspective of the history of the comic. Of particular note is the fact that the issue on Amsterdam is believed to contain the first comic strip published by Charles Boost. Focusing on Amsterdam’s dislike of Mussert, it is a comic strip that – without using speech balloons – tackles a theme that ultimately left deep scars in the collective memory, following the outbreak of the Second World War later that year: the Nazis’ increasingly rabid, merciless anti-Semitism.

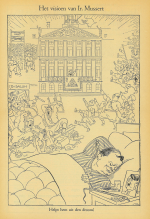

Not only does the comic strip cover, at breakneck speed, Mussert’s visit to a party colleague in the community ‘het Blauwe Zand’ in the strongly left-leaning district of Tuindorp Buiksloot in 1937, but it also shows the NSB members’ attack on the ‘Koco’ Jewish ice-cream parlour in the spring of 1939 (a subject that Jordaan also referred to in his cartoon ‘The vision of Mussert’ in the same issue). The third frame depicts the vandalising of the stone bust of the Jewish playwright Herman Heijermans, carried out in January and February 1939 by the National Socialist splinter group known as the ‘Iron Guard’ – as historian Gertjan Broek has shown.

The final comic frame probably refers to the same group’s smashing of the windows of Samuel Citroen’s home, the base of the liberal Vrijheidsbond. It is a depiction of contemporary political events that not only demonstrates this medium’s potential to capture political issues visually, but also impresses on today’s reader that anti-Semitism was not ‘just’ a foreign phenomenon that was imported into the Netherlands with the German invasion of May 1940.

A version of this article has been published in Stripschrift nr.477.