- Herengracht 380. Nieuwe huisvesting voor het Rijksinstituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie: ter gelegenheid van de ingebruikneming op 22 september 1997 na de restauratie, renovatie en uitbreiding 1996- 1997, The Hague: SdU 1997;

- P.A.H.M. de Wijs, Het Huis Herengracht 380-382 Amsterdam, Hilversum: Stichting Architecten G.B. and A. Salm, 1986;

- Jan Luiten van Zanden and Daan Marks, Koelies, planters en koloniale politiek. Het arbeidsregime op de grootlandbouwondernemingen aan Sumatra's Oostkust in het begin van de twintigste eeuw door

- Widjajanti Dharmowijono, Van koelies, klontongs en kapiteins: het beeld van de Chinezen in Indisch-Nederlands literair proza 1880-1950 (dissertation).

If the Walls Could Speak

The Unlikely History of Herengracht 380-382

The history of the monumental building on Herengracht 380-382, which today houses the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, is linked in an unlikely way to the institute’s field of research: Germany, the war, the looting of artistic and cultural property, the liberation by the Allies, the special tribunals to try war criminals after the Second World War, and – not least – colonialism in its worst form.

The colonial fortune of Jacob Nienhuys

This national monument, built between 1888 and 1890, was designed by the then celebrated architect A. Salm (1857-1915). The building was constructed in a medley of styles, with the exterior of an early sixteenth-century French castle and rooms in ‘national’ historical styles.

It was commissioned by Jacob Nienhuys, a wealthy and powerful tobacco magnate who wanted a building that was ‘different from anything built before.’ And that was what he got – complete with electric lighting, the first residential home to benefit from this in the Netherlands. It is the history of the building’s residents and users, however, rather than its architectural aspects that binds Herengracht 380-382 to NIOD in myriad ways.

The Deli Company

The story begins with Jacob Nienhuys, who was the first to move into the building in 1891, together with his wife and five children, a nanny, a lady companion, two maids, a groom and a coachman. The coachman and his family of six lived on the upper floor of the coach house. The fact that Nienhuys could afford the luxury of such a palatial home was thanks to the enormous fortune that he had managed to amass in the Dutch East Indies; something he had done – to put it euphemistically – in a none too gentle a manner. Born in 1836, he had left for the colonies at a young age to try his luck. This brought him to Deli in East Sumatra, where he established a tobacco plantation with his business partner, Peter Wilhelm Janssen.

They were granted a concession by the Sultan of Deli in 1869, clearing the way for the ‘tobacco cultivation society’ known as the Deli Company (Deli Maatschappij), half of the shares of which were owned by the Netherlands Trading Society (Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij). The founding of the Deli Company marked the start of the extremely profitable business of tobacco cultivation on Sumatra and the related development of the area, particularly the city of Medan.

The Deli Company became one of the largest colonial crop-cultivation firms in the Dutch East Indies. In the last decades of the nineteenth century, the company was operating no fewer than 120,000 hectares. The success of the trade rested in part on the quality of the tobacco, especially for cigars, but it was also due to the labour system that had been introduced by Nienhuys and that would continue to exist for practically the whole colonial period: the system of coolie labour.

Coolie labour

As the local population, the Batak people – whom Nienhuys described as ‘a stupid race, on the whole’ – refused to work on his plantation for the wages he was offering, and as the area was also sparsely populated, Nienhuys employed migrant contract labourers, ‘coolies’, from Java, China and India. He did this for the sake of lower wage costs, not because he held these groups in any higher regard.

On the contrary; in his view and that of his colleagues, the Chinese were bold arch-swindlers and the Javanese were lazy and hot-tempered. When a single European faced a hundred coolies, there was thus a need for though discipline. And it was precisely this power of discipline that plantation owners were legally granted under the so-called ‘coolie ordinance’ of 1880.

What developed in the ‘Wild East’ of Sumatra in those years was nothing less than a system of serfdom that came close to slavery. Frequently lured under false pretences, the coolies signed a contract, often for three years, in exchange for prepayment of their wages. By concluding the agreement, they de facto surrendered all rights as citizens. They became subject, both legally and economically, to the power of the person for whom they worked.

Part of the coolie ordinance was the so-called poenale sanctie (penal sanction), an already existing arrangement whereby in the case of a breach or alleged breach of the labour agreement, the planter could punish his coolies without restriction in the way he saw fit, including fines and corporal punishment. This made the planter both policeman and judge; he could hand out punishments for all kinds of offences, such as ‘laziness’, ‘affront’, or running away from the plantation.

These punishments took various forms, starting with a beating, but not infrequently culminating in excessive violence. Shortly before his death in 1927, the very elderly Nienhuys was still full of praise for the system he had helped to create. In the words of Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indie [The East Indian Daily News]̈:

According to its architect, it became the most important factor behind the success of his enterprises. ‘Deli owes its flourishing to this system of governance, to a great extent; the scheme is the inner strength that the Sumatra planter can nurture in order to deliver a tobacco harvest that has been produced well in every respect.

It was precisely this kind of ‘hard-work-and-rough-diamond-prose’ - to quote the writer and journalist Rudy Kousbroek, adapted from his older colleague E. du Perron - that permeated the literature and the historiography for a long time; indeed, for a very long time.

From Het Nieuws van den Dag voor Nederlandsch-Indië, 2 november 1929. View the original source in Delpher.

An abominable system

The fact that a large-scale system could have arisen on the plantations, far from the central authority in Batavia, based on coercion, violence, racism and arbitrariness, did not seem to get through to the world, despite several alarming publications around the turn of the century.

Or, to put it more accurately, the truth was not allowed to come out. In 1903, a scathing report by the prosecutor in Batavia, J.L.T. Rhemrev, commissioned by the Governor General following earlier revelations, was swiftly hushed up by the Minister for the Colonies, A.W.F. Idenburg. The report remained secret; even the Dutch House of Representatives did not see it, something to which its members acquiesced. Only much later would the research be taken up once more.

Nevertheless, these first shocking publications were not greeted with total silence. From the 1920s, in particular, there was heated debate about the coolie ordinance and the poenale sanctie in politics and the media, but without consequences for the time being. In the end, the poenale sanctie system would not be abolished until January 1942. By that time, one should add, the Deli Company had already abandoned the system in order to avoid an imminent ban on tobacco imports in the US.

Read more about these publications in the article Een advocaat van kwade zaken. Het koloniale milieu aan Sumatra's oostkust in de eerste decennia van deze eeuw by Jan Breman in De Gids from 1992.

After the decolonisation of Indonesia, this period of history fell into oblivion, only to be wrested free again many decades later. For in the dominant account of colonial history, there was no place for what Kousbroek has described as ‘a history of suffering on such a colossal scale that it is indescribable, but also of the extensive ramifications and complicity in the way in which the whole of the Dutch East Indies was governed.

Even at the end of the twentieth century, many in the Netherlands continued to play down the very worst aspects of the coolie system, as the sociologist Jan Breman would discover in 1987 upon the publication of his critical study Koelies, Planters en Koloniale Politiek [Coolies, Planters and Colonial Politics], in which the Rhemrev report was printed in its entirety. Breman was accused of raking up ‘excesses’.

Rudy Kousbroek said this at the presentation of the republication of the Rhemrev-report in Het Oost-Indisch Kampsyndroom. Amsterdam: Atlas 1992.

The same mechanism could be seen at work in the admiration for men such as Jacob Nienhuys, the founder of the Deli Company. In any case, the persistent rumour that he had had to leave Sumatra in haste in 1869 in order to avoid charges for flogging seven coolies to death was never something that was held against him, not during his lifetime nor later. It did not feature in the historiography of the Deli Company, or in the booklet that NIOD published in 1997 when it moved into the premises on Herengracht.

Nor did the story play a role in 1913, when the initiative was taken in Medan to build a fountain to commemorate the fact that fifty years previously, Nienhuys ‘had set foot ashore in Deli for the first time, and through his entrepreneurial spirit, despite having to overcome major difficulties, had laid the foundations for tobacco cultivation in this region'.

It was precisely in relation to this monument, however, that the accusation of murder surfaced. The story, for which no corroboration in the archives has been found to date, had evidently been doing the rounds for decades, as can be inferred from an article in the Sumatra Post, published exactly one week after the announcement of the initiative to build the fountain:

In 1867 or 1868, Nienhuys was accused of flogging seven coolies to death. The case was not investigated further at the time, but Mr Nienhuys was given notice on behalf of the Sultan that he would have to leave the country, which he did. Mr Nienhuys would never return to the Indies. [...] in 1875, on the request of the Deli Company, another investigation was ordered by the government into what had happened in ‘67 or ‘68 under Mr Nienhuys’ management. This investigation was also led by an inspector, but it could not find proof that the alleged crimes had not been committed.

Nienhuys himself, supported by others, gave a very different reason for his hasty departure for the Netherlands in 1871: his deteriorating health.

Upon his return, Nienhuys lived in Baarn for many years, before buying the substantial canal house on Herengracht 382 in 1887, designed in 1775 by Jacob Otten Husly. He had the building renovated, but just before the renovations were complete the building was struck by a fierce fire, caused by ‘drying out’. As a result of the severe frost, the fire-extinguishing water froze, creating a spectacular vision, according to one newspaper.

According to the the chair of the Municipal Council of Medan at the unveiling in 1915, as can be read in the Sumatra Post of 17 november 1915. The monument was demolished in 1958. Read more about the unveiling on the website Koloniale Monumenten.

From the Sumatra Post of 14 May 1913, as cited in the article 'Het beest aan Banden? De koloniale geest aan het begin van de twintigste eeuw’, in: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (1988). You can read the article online here.

Nienhuys thereupon decided to build a completely new house that would also incorporate the plot next door (number 380). The new building had a classic lay-out, with the exception of the entrance, which was located on the right-hand-side in order to allow the coach to drive in. On either side of the uppermost dormer were two statues of Mercury and Minerva, the symbols of Trade and Civilisation.. Nienhuys would live on Herengracht until 1909. In the following year, he transferred the premises to the Maatschappij tot Exploitatie van Kantoorlokalen (‘Society for the exploitation of office spaces’). In subsequent years, the address was home to organisations such as Broekman’s Effectenkantoor and the Nationale Borg-Maatschappij, which still exists today.

In German hands

In 1921, the Amsterdam branch of the Deutsche Bank took up residence in the building. This saw the installation of two underground storeys for vaults, now an archival repository, for which the garden was sacrificed. A bank reception hall was built above the vaults. Radical changes were also made elsewhere in the building. For example, the flower paintings on fabric that had decorated the stairwell were removed in order to create a more modern, business-like ambience.

With the beginning of the German occupation of the Netherlands, the building was appropriated by the occupying forces, like many other distinguished buildings on the canals and in the neighbourhoods around the Museumplein and the Vondelpark. In May 1940, the Reichskreditkasse moved into the ground floor, including the vaults, whilst the Feldluftzeuggruppe Holland took up residence on the first, second and third floors. This administrative unit was responsible for supplying the German air force, but its duties also included the disassembling of unexploded aerial bombs.

The service left the building in June 1940, whereupon the Verbindungsstelle des Generalluftzeugmeisters moved in. The floors retained their link with aviation with the establishment of an office of Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG, the aircraft and engine manufacturer that the Nazis had made completely subservient to the war machine. Junkers manufactured the notorious Stuka bombers, for example.

In the spring and summer of 1941, the office building also housed the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), the special taskforce led by Hitler’s most important ideologist, Alfred Rosenberg. In 1934, as ‘Beauftragte des Führers für die Überwachung der gesamten geistigen und weltanschaulichen Schulung und Erziehung der NSDAP’, the latter was tasked with the training and education of the party.

This included founding an institute for the study of the ‘Jewish question’, the Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage in Frankfurt. Shortly after the invasion of France, Rosenberg decided to found the Einsatzstab with the goal of systematically gathering books, archives and other cultural goods, especially those belonging to Jews, in German-occupied countries and transporting them to Germany. The service was also responsible for destroying ‘verboden lectuur’. Offices were soon opened in Belgium and the Netherlands, and later in other occupied countries, too.

Deutsche Bank announced their new branch at Herengracht 380 in an advertisement in newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad on 4 July 1921.

For example, the spectacular controlled explosion of an English bomb on Paramariboplein in Amsterdam on 19 August 1940 made all the papers. For more on the tasks of this service, see the introduction Luftzeuggruppen on the relevant archives in the Bundesarchiv.

Patricia Kennedy Grimsted made an overview of these archives in her work A Survey of the Dispersed Archives of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), digitally available here, including a comprehensive bibliography.

Rosenberg’s dream was the formation of an enormous collection that would serve the institute’s researchers as raw material for the study of the ideological opponents of Nazism; not only Jews, but also Freemasons and all kinds of democratic and socialist organisations. Although the EER was not alone in its looting activities, Rosenberg’s organisation played a special role because the Reichsleiter had received personal authorisation from Hitler.

In the following years, no fewer than 1.5 million railway trucks of goods would be carried off to Germany: whole libraries and archives, collections relating to music and religion, paintings and statues, and the inventories of churches and synagogues. In the Netherlands, among others, the Spinoza library in The Hague and the Spinozahuis in Rijnsburg, the acclaimed Rosenthaliana library and the International Institute for Social History (IISG) would be stripped. In August 1941, the headquarters of the Einsatzstab moved into the now-gutted building of the IISG on Keizersgracht. It was from there that the organisation would direct the massive looting of the possessions of deported Jews.

Employment in Germany

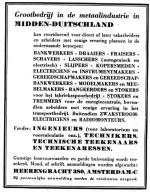

From 1941, Junkers’ office also appears to have played an active role in attracting volunteers for the Arbeitseinsatz. Whilst in 1941 the company was still mainly posting personnel advertisements for its own office, in 1942 the office on Herengracht 380 undertook repeated and widespread recruitment for all kinds of positions in Germany.

At the beginning of 1943, the advertisements ceased: the defeat in the Battle of Stalingrad had brought a definitive end to the era of ‘volunteering’. From now on, as part of the German ‘total war’, hundreds of thousands of Dutch men were drafted for the Arbeitseinsatz, on pain of arrest, jail or concentration camp.

Liberation and war tribunals

Due to the presence of the vaults, the building’s role was more or less predetermined: in May 1945, the First Canadian Army Leave Centre put the ground floor into use as its Pay Master Office. The building thus became home to the army’s payments system. Around the same time, the vaults were also put into use by the Dutch State Treasury Agency of the Ministry of Finance.

Six months later, Herengracht 380 – now no longer written as ‘Heerengracht’ – became the seat of one of 19 tribunals that were established as part of the special post-war justice system, to try ‘less serious crimes’ that had been committed during the war. The system had been planned in London by the Dutch government in exile as early as September 1944. The tribunals were not concerned with criminal law, but with what one might call ‘disciplinary law’; behaviour that could be described as immoral or treacherous. Specifically, these were mainly Dutch citizens who had belonged to national socialist organisations, taken advantage of enemy measures, or failed to comply with the measures issued by the government in exile.

The Amsterdam tribunal had no fewer than 25 courtrooms, presided over by a jurist – not necessarily from the judiciary – and two other members who were ‘well regarded in the field in which they passed judgement.’ Thus, the tribunal was not a weighty judicial body, but rather a form of lay justice.

According to newspaper reports, the tribunal took up residence in the building in the first week of January 1946, but it would be months before the first cases were tried. Many suspects awaited trial in internment camps and prisons. Calls were published in newspapers to come and testify before a tribunal or the Special Court, which handled more serious crimes

These were not war criminals, in other words, but people who were guilty of less serious forms of collaboration. “They are not your usual suspects. For the most part, they are elegantly-dressed gentlemen, who have the air, even now, of having been misunderstood, and behave as though they were completely in the right,” wrote the Christian national weekly De Spiegel in June 1946.

The tribunal could impose a number of measures, varying from internment (up to a maximum of ten years) to the removal of certain rights and the confiscation of assets. One should add that the convictions were only given force of law when they were confirmed by the ‘high authority’ that the government had appointed for this purpose. The double-check was there for a reason, as it was impossible to appeal against a ruling.

Read more about this judicial system in the dissertation of Paul van de Water, Collaboratie en Geweld. Radicalisering en extremisme tijdens de Duitse bezetting in Nederland.

Read, for instance, the original newspaper articles about the installation of the tribunal in Het Parool and De Waarheid in January 1946.

Not only the tribunal itself, but also the Dienst Voorlichting Bijzondere Rechtspleging, the information service for the special tribunals, was housed in the building at this time. And here we encounter a very direct link with today’s NIOD, for the information service was in close contact with what was then known as the Rijksinstituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie (the State Institute for War Documentation, RIOD), including on the production of the reference work Documentatie. Status en werkzaamheid van organisaties en instellingen uit de tijd der Duitse bezetting van Nederland [Documentation. Status and activities of organisations and institutions at the time of the German occupation of the Netherlands] – still widely used today.

Moreover, the information service took the initiative to ask prominent detained SS officers and NSB members to write exposés of all kinds of organisational matters at the time of the occupation, specifically in order to aid RIOD’s work. These reports are kept in the NIOD archives. The tribunals were disbanded on 1 June 1948 and their tasks were assumed by regular magistrates’ courts. All in all, they had heard almost 50,000 cases. From that year, the Raad voor het Rechtsherstel (Rehabilitation council) and the Tuchtrechter voor de Prijzen (Disciplinary court for adjudication on pricing offences) would be established on Herengracht.

You can read this reference work online here on Delpher.

From the Dutch State Treasury Agency to NIOD

In 1948, Herengracht 380-382 was bought by the Nederlandsche Bank. Until 1965, the premises served as a multi-tenant building for a number of offices, including those of the Dutch State Treasury Agency of the Ministry of Finance, the secretariat of the municipal rent tribunal and the Nederlandsche Bank itself. The building was sold to the state in 1965 for the sum of one million guilders, after which the entire premises was put at the disposal of the Dutch State Treasury Agency of the Ministry of Finance.

In 1978, the palatial building was renovated and restored by the architectural firm Snieder, Duyvendak and Bakker, at the behest of the Ministry of Finance, in order to serve as the quarters of the Dutch State Treasury Agency of the Ministry of Finance and the Grootboeken der Nationale Schuld (National Debt Office). These renovations saw the addition of the copper ring in the stairwell, with its horizontal static and ‘eternally turning’ vertical components.

The building was opened on 24 March 1980 by the newly-appointed Minister of Finance, A. van der Stee. An independent organisation, the Treasury Agency presented itself as a ‘detached post of the ministry in the financial centre of the Netherlands.’ Its most important tasks lay in the field of management of national debt and advising the minister on developments in the financial markets. In 1993, the Treasury Agency was forced to leave the building due to a lack of space and ‘overload resulting from computer use’.

The state initially planned to sell the building, but the plan was abandoned in view of its unique historical character. The hunt was on for a suitable tenant, and it was not long before the searchers alighted on NIOD, then spread across three buildings in the vicinity. The availability of the vaults as an archive repository seemed a particularly attractive option.

It soon proved that substantial adjustments and renovations were needed, and in the same year a new restoration and renovation plan was drawn up by the Dutch Government Building Department. The plan included the restoration of the nineteenth-century character of the interior on the monumental floors and the creation of a new reading room and library on the site of the former garden. The restoration was undertaken by the architectural firm De Kat & Vis, whilst Benthem Crouwel Architekten were responsible for the new building.

On 22 September 1997, the building was officially opened as the new home of the organisation that was then still formally known as the ‘State Institute for War Documentation’, but renamed two years later as the ‘Netherland’s Institute for War Documentation’ (NIOD). Since 2010 it is officially called the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

Literature list

Colophon

Text

Frank van Vree

Advice and contributions

Jon van der Maas

Harco Gijsbers

Hubert Berkhout

Paul van de Water

Online editing

Katie Digan

This longread was previously published on the Niod website in 2018.